The Port of Quebec neighbourhood round tables — where listening is on the menu

CommitmentAt the start of this year, the Port of Quebec launched a citizen consultation pilot project that is off the beaten track. It has set up neighbourhood round tables to establish direct dialogue with citizens, outside the channels already in place.

“We wanted a friendly activity that allowed people to express themselves,” explains Eloïse Richard-Choquette, the port’s director of community relations.

The tables don’t have the same well-honed meeting mechanism normally found in the form of a committee. It is rather more of a collective intelligence workshop.

There we really wanted to create a link, then a dialogue, so that people are comfortable discussing things with us, putting themselves in a constructive mode and collectively looking for solutions.

It’s a new exercise that adds to the toolbox of the community relations team without replacing existing collaborative structures, such as the Quebec Port Authority (QPA) cohabitation committee, or the vigilance committee established by the city.

“On the contrary, we take what emerges from the neighbourhood round tables to the cohabitation committee so that its members can further enrich these ideas with their expertise.”

The tables also emerged from the requests of citizens, who didn’t know, in some cases, to whom they should refer and did not feel heard by the port. “These are really 100% new people, as these are not folks that we are accustomed to meeting in other committees,” confirms Florence Bisson, a QPA community relations advisor.

Florence Bisson at a community activity organized by the Port of Quebec. / Florence Bisson lors d'une activité communautaire organisée par le Port de Québec.

Bisson was responsible for initially sounding out citizens before launching the project to gauge the pulse of opinions. She circulated a survey on social networks to obtain comments from citizens, as well as their interest in participating at the tables. She also went through all of the received reports to compile a list of the concerns.

“We didn’t want to go into these meetings with no idea, but rather to have some notion about what we’d be discussing,” explains Bisson.

So, by asking people directly about their concerns, it also made it possible to know what we wanted to work on, to start a conversation.

The port did not embark on this unique project on its own. It called upon an external consultant, Anaïs-Monica McKay, M.Sc., a strategic consultant and facilitator in innovation and collaboration processes. As a resident of the Quebec City borough of Limoilou, she thought hard before accepting to be a part of this pilot project. “I didn’t apply for this role; Éloïse called me,” she relates.

“We first off extensively discussed the ethics of my involvement, how I could facilitate a process that really concerns me as a mother who lives in Limoilou,” she explains. “I also questioned what impact it would have on my business if my role as an independent facilitator was misunderstood.”

The community relations team’s commitment ultimately convinced her to take part. “I love working with Éloïse and admire the courage she has to stick herself between a tree and its bark,” she says. “What interests me about this mandate is the particular stance taken by the team: a space of mediation and openness between what the public firstly needs and then what the company is seeking,” McKay adds.

When I present ideas to these gals, they get on board, really go for it and, above all, push hard to move things forward.

Open-forum concept

The port has created three neighbourhood round tables, one for each of the sectors on its territory: l’Anse au Foulon, Beauport and Limoilou, and the estuary. Although there are common issues throughout the territory, the concerns aren’t the same, and the port sees added value in proceeding by geographical area. “For example, cruises do not affect Beauport, and no one in the estuary region talks to us about Beauport’s bay,” Richard-Choquette notes.

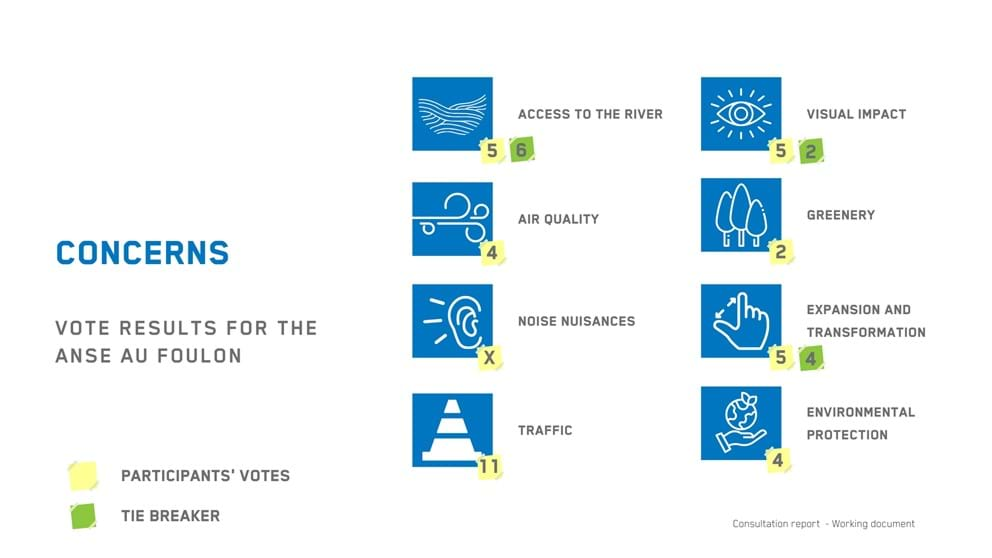

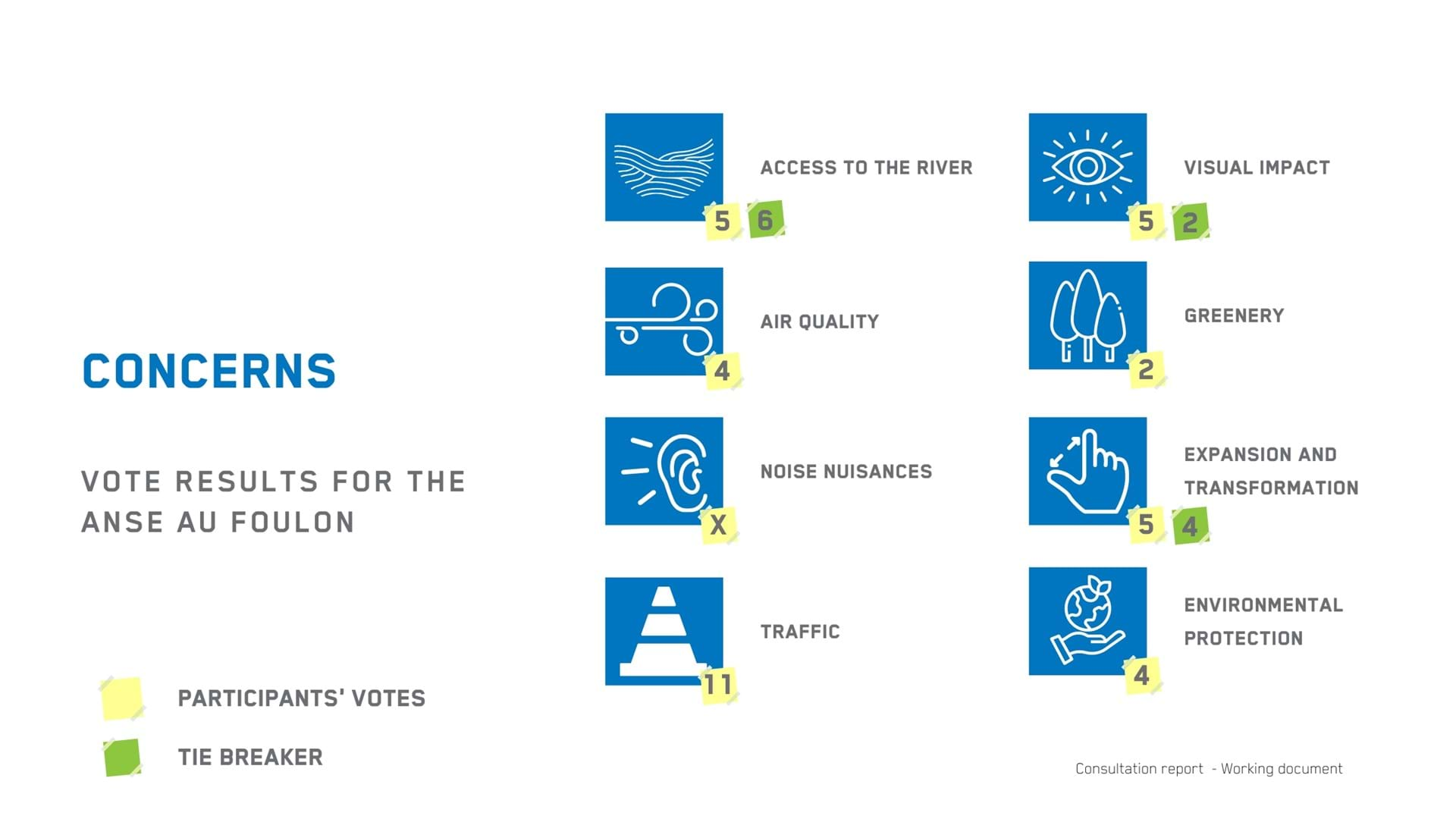

While the tables are based on an open-forum concept, the port has taken the process a step further. Citizens decide what goes onto the agenda. After the team initially compiles the list of concerns that have been raised by citizens, the item that comes up most often is immediately one of the subjects up for discussion. The team next submits all the raised themes to the individuals present, who each choose four priorities. The votes are then all counted, and the three most selected topics are put forward. Topics set aside are still displayed on a board and citizens can add their comments to them if they wish.

Out of the eight possible themes at the Anse au Foulon table, the discussed issues were access to the river, expansion and transformations, traffic, and (at the top of the list) noise.

Participants are free to move from one board to another to discuss matters with each other and with a port representative. They are invited to share their concerns and irritants, but also to propose solutions.

“Of course, there was a certain anxiousness on our part before the very first meeting, because this was all new for us,” recalls Richard-Choquette.

Yet it surpassed our expectations, with people being very positive and constructive in their approach. They appreciated being heard and us then having the discussions with them.

Even within the Limoilou sector, where relations with citizens are particularly tense, the discussion was constructive. McKay feels that even though everyone arrived with his or her vision, the profound dialogue resulted in everyone leaving having learnt something from the discussion: “In Limoilou, people are very informed and mobilized, which led to an extremely rich conversation on different points of view.”

After each of the tables is held, the community relations team offers feedback on the activity to the participants with a summary of the discussions: the issues raised, the possible solutions put forward, next steps along with the plans for subsequent meetings.

So the work doesn’t end here for Mckay or Richard-Choquette’s team. The initial encounters are just the first basis for an open discussion that can evolve both internally and with citizens. “My role is both to facilitate dialogue with citizens and to equip the team so that it can work in synergy with both the community and the port’s various departments,” McKay says. “This is a delicate mandate for me, but absolutely stimulating given the complexity of the challenges and issues.”